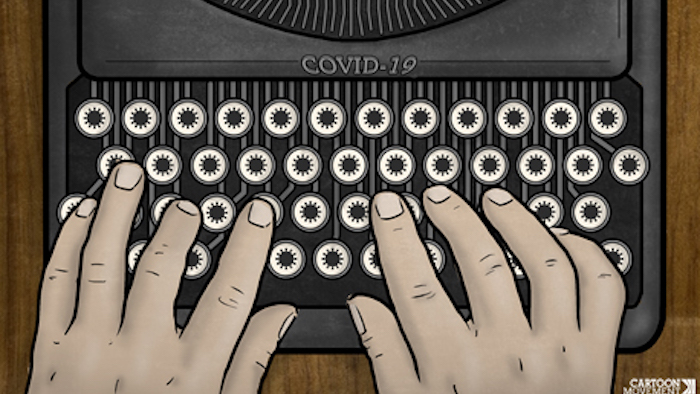

From genocide accusations to alleged cures, the coronavirus pandemic is accompanied by a swathe of conspiracy theories. These are perpetrated not only by clickbait websites but also authoritarian regimes who exploit the crisis for political purposes and try to shift the blame from their inadequate responses. An international survey and a detailed case study.

Conspiracy theories and rumours often spread in the wake of negative events, especially if these events are new and partly unknown. This is exactly what happened in the case of the coronavirus.

The problem goes well beyond the clickbait disinformation sites. While the Hungarian police cracked down on some disinformation sites spreading panic about the coronavirus, the Hungarian government, especially at the first phase of the epidemic, used its media empire to spread disinformation themselves about the sources and origin of the crisis in a strong communication scapegoating effort.

Corona – the king of disinformation

As fears about the coronavirus spread worldwide, disinformation campaigns are becoming more and more efficient. Besides clickbait websites aiming to earn a profit off spreading false and sensational information about the virus, geopolitical actors interested in sowing information chaos have also entered the ring. As a WHO official summarized: there is an “infodemic”, at least as much dangerous than the virus itself, as disinformation spreads faster and easier, causing huge damage.

Disinformation not only leads to false beliefs. It can cost lives and lead to social unrest. Two dangerous ways of spreading disinformation about the virus can be banalization/denial and exaggeration/panic. In South Korea, for example, we saw the former case, where a closed sect of 200 000 members denied the existence of the coronavirus and assumed that its invention is only a governmental conspiracy, which significantly contributed to the spread of the virus, resulting in many deaths.

A successful example of stirring panic could be observed in Ukraine recently. A fake chain letter was sent in the name of the Ministry of Health stating that the coronavirus had appeared in Ukraine. The hoax reached a large proportion of the population which caused smaller protests and some violent clashes, with protesters even storming a bus arriving from China. There is a strong suspicion that this piece of disinformation was helped by Russian efforts.

There are even more obvious cases: Russian sources spread many false, contradicting narratives about the coronavirus, both denying its existence and claiming that it is a biological weapon of the West at the same time. US Assistant Secretary of State for Europe and Eurasia Philip Reeker named Russia as one of the sources of coronavirus-related disinformation narratives.

Other authoritarian regimes were pretty active in spreading such false narratives as well. The most striking case is China, where the virus started. From the very beginning, some disinformation pieces spread by Russia and China wanted to pin the responsibility for the virus on the United States, claiming that they created it as a biological weapon. This narrative has even been refrained by high-level Chinese officials recently, as Chinese diplomats called the US the source of the virus, with the spokesperson of the Information Department at the Chinese Foreign Ministry claiming that ‘It might be the US army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan.’ This blatant lie aims to divert the blame away from the Chinese Communist Party – the political actor that is primarily responsible for the global spread of the virus from the very beginning.

Iran is probably the most important example of how the typical reflexes of authoritarian regimes, denial and state-sponsored scapegoating, along with ignorance of the crisis itself, can lead to an even more deadly scenario. In order to boost electoral turnout to legitimize the regime, the governmental propaganda practically denied the existence of the virus, claiming that it’s only the US dramatizing news on the virus, in order to suppress voter turnout. In line with this conspiracy theory, they stepped up against citizens and media outlets. The outcome is well-known: about 14 000 official coronavirus cases and almost 800 deaths – and the real figures must be multiple times more.

Hungary: a hybrid disinformation landscape

In Hungary, we could observe two types of disinformation. On the fringe are clickbait disinformation sites which exist in every democratic society, abusing the freedom of speech and challenging mainstream narratives. But the mainstream is also involved: directly government-run and pro-government media outlets form a choir with official governmental statements. The latter group of disinformation shows similarities with the state-sponsored disinformation of the authoritarian states discussed above.

Disinformation messages on clickbait sites

The main culprits in disseminating disinformation about the coronavirus at the beginning were online portals looking to financially profit from the situation. Their main source of income are advertisements. Large multinational companies’ commercials can often be seen running on these sites via, for instance, Google Ads.

We selected 12 influential disinformation Facebook pages from Hungary, with more than 1 million followers overall, and monitored their contents and spread of messages with the help of SentiOne’s social listening software(1).

Inforgraphics based on Political Capital’s data, produced by Attila Bátorfy / ATLO Team.

The posts shared by the 12 sites generated considerable attention. The 200 posts triggered over 21 000 interactions, 3 700 comments and 22 000 shares (as of 27 February). The high number of shares is especially concerning because it probably helped these narratives reach an even larger number of social media users. Based on the number of followers that these pages have and interaction data, we have reason to believe that the disinformation narratives we uncovered may have reached hundreds of thousands of Hungarian speaking users.

And what were these narratives?

We found four broad categories of fake news being spread about the Covid–19 outbreak.

The first group consists of ‘genocide theories’ suggesting that someone is deliberately spreading the virus intentionally to achieve a certain goal. The most typical narrative in this group claims that the ‘global elite’ – including, among others, Bill Gates – is seeking to decimate the population of the Earth. The ‘Bill Gates theory’ was even brought up by the pro-government Demokrata portal, but usually was more popular on the fringe clickbait sites. This theory has a populistic narrative.

The second group includes ‘biological weapon theories’, something we have also mentioned above. Typical theories in this group claim that a biological weapon is being used against China in a ‘Third World War.’ One specific narrative claims, for instance, that the US is behind the outbreak to ‘bring the Chinese economy to its knees.’ This narrative fits perfectly into the well-known geopolitical narrative often disseminated by Russia and China that suggests the US acts in a hostile manner against all of its perceived rivals, even if it means breaking international conventions. At the same time, conspiracy theories suggesting that the virus was spread by China and was created as a biological weapon a military lab in Wuhan were also popular. The common feature is the claim that the coronavirus is not something that occurred naturally, but would be the result of a specific plan aiming to annihilate a group of people.

The third group of disinformation is of the apocalyptic ‘end of the world’ narratives. These are articles that seek sensation with claims that can sow panic. There were claims about a civil war in Wuhan, supposing that hundreds of infected are ‘besieging’ checkpoints leading out of the area, and even that almost 5 million people have left Wuhan, so the virus has already spread throughout the world. This kind of disinformation already discussed coronavirus cases and deaths in Hungary while there were no official cases.

The last and smallest group consist of articles about ‘cures’. These wishful disinformation pieces state that an antidote to the virus has been found, traditional Chinese medicine ‘blocs’ the virus, fantasize about curing it with Vitamine C, and so on.

Most of these disinformation narratives were recognized by the Hungarian authorities as well, who have launched an investigation into the editors of over a dozen portals spreading false information about the coronavirus. These portals have been shut down and their editors are sued by the authorities. The police also arrested a vlogger, who spread the disinformation that Budapest would be placed under lockdown.

The vigilance of the authorities against these sites is encouraging, and certain restrictive measures against these sites also seem justifiable, as panic under such circumstances can cost lives. Numerous disinformation portals are spreading unsettling fake news about the coronavirus, which are reaching hundreds of thousands of people. Manipulative articles about COVID–19 are only improving these sites’ traffic, helping the dissemination of even more healthcare-related fake news and ineffective ‘cures.’ These sites are also spreading disinformation on ‘alternative medicine’ that allegedly cures everything from high blood pressure to cancer; they can promote anti-vaccination, and do harm well beyond the disinformation crisis.

At the same time, unfortunately, certain Hungarian higher authorities were not fighting disinformation, but helped in its production and spread instead. Similarly to the Iranian case, the main goal was to find scapegoats and to mask the unpreparedness of the authorities.

State-sponsored disinformation

Hungary was not the only country that met with the coronavirus totally unprepared – not even among developed countries. On 28 February, with yet no confirmed cases in Hungary, prime minister Orbán confidently claimed that the real problem and challenge for Hungary is not the coronavirus but illegal migration. The belittling of the significance of the virus later gave way to the propaganda that connects the favourite topic of the Hungarian government – illegal migration – to the virus.

The grand narrative about the connection between the coronavirus and illegal migration was first promoted by the chief internal security adviser to the Prime Minister, György Bakondi. He said in early March that there is a ‘certain connection between the coronavirus and illegal migration.’ He added that most arrivals of the illegal migrants are from Afghanistan, Pakistan or Iran, so most of them are from, or passed through, one of the main centres of the epidemic. Therefore, the infamous ‘transit zones’ stated automatically rejecting all migrants from the southern border. This was the first important sign that the central administration itself started to exploit the epidemic for its own political gain.

Later, the Prime Minister fell in love with this plot as well, promoting it domestically and internationally as well. In line with these arguments, Hungarian officials were busy pointing their fingers at patients with coronavirus in migration camps. Also, the first publicly announced cases of coronavirus were of Iranian students, with the Hungarian government, responsible authorities and Fidesz loudly blaming them for the lack of cooperation during the quarantine – a message that deliberately aimed to strengthen the association between the coronavirus and Muslim immigration.

These messages were absurd. The Iranians who tested positive in Hungary were not illegal immigrants, but students studying in Hungary with a Hungarian state-supported fellowship program. But beyond that, how could an epidemic spreading throughout the world’s elites following flight routes, infecting officials such as the mayor of Miami, the wife of the Canadian Prime Minister, the spokesperson of the Brazilian President, and Tom Hanks as well, be blamed on illegal migrants?

Pro-government pundits were parroting the message that ‘migrant countries are primarily affected by the crisis’ – whatever the expression ‘migrant countries’ may mean –, and blaming the virus on western Europe. And, of course, on George Soros and his theory of the open society. At the same time, no one on the governmental side put any blame on China, the source of the virus – probably to defend their political and economic connections with China.

The spokesperson of the Hungarian government blames the press for the lack of fact-checking, and subtly threatens journalists, claiming that the government will take every measure to stop the flood of fake news and rumours.

After a period of denial and slow responses, the Hungarian government recently finally took several important restrictive measures to slow down the spread of the virus, which point in the right direction. Still, this crisis is the biggest challenge that Orbán experienced during his 14 years of governing so far. Not only because of the economic slowdown and the casualties that every European country faces. But also because the crisis hits hardest the sectors – healthcare and education – that were hit hardest by the Hungarian government’s fiscally restrictive policies, in a period of otherwise massive growth.

The Orbán regime is terrified of the political impacts, and its blame-seeking disinformation campaign was aimed at channelling the discontent elsewhere. Orbán got used to a way of governance when, standing on strong economic fundamentals, he could get away with anything simply with political communication and symbolic politics, relying on a huge and extremely centralized media empire. The first weeks of grappling with the pandemic show that this tactic will be extremely difficult to employ this time.

The authors are researchers of Political Capital Institute. The original social media study in Hungarian can be found here.

(1)

The profiles of these pages vary between general clickbait sites (Mindenegyben blog), to anti-vaccination sites (Oltáskritikus Életvédők Szövetsége). SentiOne found 8 478 articles between 11 January and 11 February, the majority of which were posted by mainstream media. The 12 sites selected were responsible for 200 of these. Their interest in the virus started to increase around 26 January and fell considerably by the time our research ended on 11 February. However, when news came about the deteriorating situation in Italy and South Korea in late February, their interest peaked once more.