Three hundred fifty years after the Great Viennese Plague and 75 years after the moral and material disaster of World War 2 and the Holocaust, Vienna’s landmarks are helping inhabitants come to terms with Corona. Or are they really?

In 1679, Vienna was haunted by one of the last major plague epidemics in Europe. Nearly 80,000 Viennese are estimated to have fallen victim to the bubonic plague, which thrived among rats and malodorous mounds of waste. Like many other trading metropolises at the time, the capital of the Holy Roman Empire was overcrowded and lacked proper sewers. Social distancing and careful hand-washing were yet to be an enforceable reality.

No wonder Emperor Leopold I wanted to get out. But before he fled from the poshest palaces of the Habsburg House, he promised to erect a monument to God’s mercy – if the plague would only depart and allow him to return to his capital.

Viennese High Baroque as a projection of the pandemic. Photo: ©CHeFred

Almost 15 years later, one of the finest works of the Viennese High Baroque was finally completed: die Pestsäule, the Plague Column, erected on the Graben in the middle of town. The worst of the plague was over after a year or so, but there followed the Turkish siege in 1683, referred to in English as the Battle of Vienna. After that, the column underwent a long series of aesthetic drafts and artistic concepts. The end result, inaugurated in 1693, is an intricate iconographic narrative, informing onlookers that both the plague and the Ottoman onslaught were a punishment from God, only averted thanks to the virtue and vigilance of Emperor Leopold.

The memory of the Great Viennese Plague may have faded after 350 years, but in the time of Corona its monument has gained new relevance. An epidemic is an epidemic is an epidemic…

While freedom of movement has been restricted by the Austrian government’s draconian measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, many in Vienna have defied the ban on staying in public space and made a pilgrimage to the monument in the city’s historic centre. Observed by no one but the surveillance cameras of the locked-down luxury stores, they have lit a candle or deposited a prayer at the foot of the column.

“Dear God, help us!” a child’s pale, pastel drawing exclaims. “Protect us from the Corona virus!” a young girl has written on another drawing. She has signed the picture depicting Jesus on the cross with her name: Magdalena. Perhaps one of the terrified and grieving human figures at the foot of the cross is Magdalena herself? Not the Biblical Mary Magdalene, but a frightened girl in 2020 Vienna. In any case, there is a lot of childish anxiety in those blood-red, sad emoji mouths. From the scary sky above, coronavirus cells fall like thorny raindrops.

Around the corner, just a stone’s throw from the Plague Column, is St. Stephen’s Cathedral – Vienna’s most famous landmark, with a place in the hearts of most of the city’s inhabitants. Steffl, as it is affectionately called, is a symbol of how the Austrian capital has managed to recover some of its historic splendor, as well as some normality, after the material and moral misery of World War II and the Holocaust.

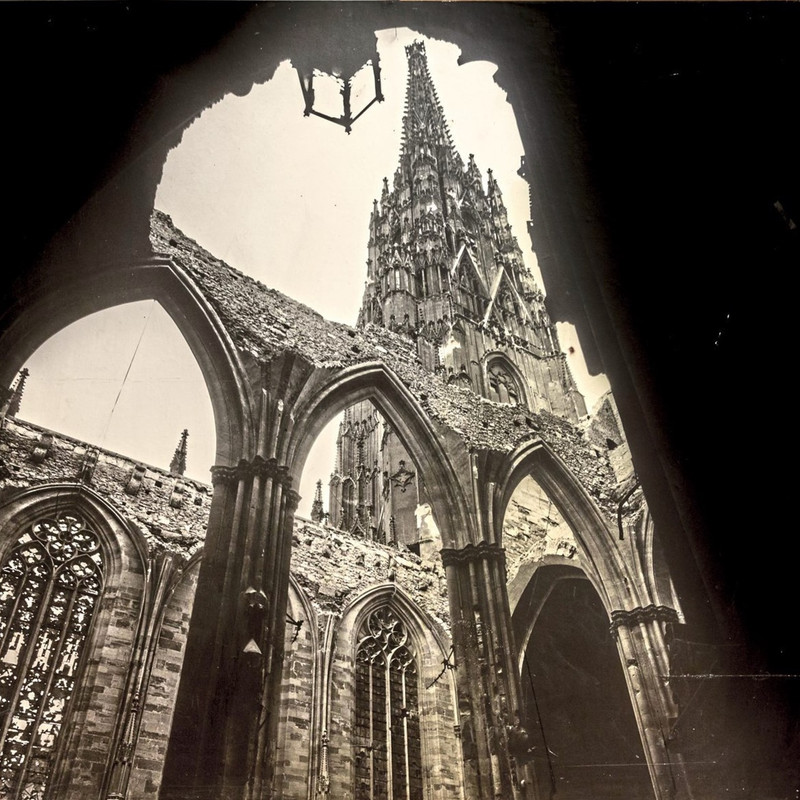

In another Battle of Vienna, the so-called Vienna Offensive in April 1945, St. Stephen’s was severely damaged; the roof chair collapsed, and only a small portion of the church remained intact. Upon entering, you could look straight up and see a sky just as frightening as the one on Magdalena’s drawing. But the Viennese finally repaired their Steffl, and this year, on Easter Day, April 12 – exactly 75 years after the devastating fire – they had planned to celebrate a very special Easter Mass.

On 12 April 1945, the St. Stephan’s Cathedral was in ruins. Photo: ©Domarchiv St. Stephan

It was indeed special, but not in the way that was intended. Just as Pope Francis in St. Peter’s in Rome celebrated mass all alone, Austria’s Cardinal Schönborn held Easter mass before the echoing vaults and empty benches of St. Stephen’s Cathedral.

Almost empty.

Instead of thousands of churchgoers, photos of believers lined the pews, often obscured by swirls of incense but still discernible on television screens. In his sermon, broadcasted live, the Cardinal invoked that gaping hole to the sky: now, like 75 years ago, we’ll need to develop and lead lives of virtue to face Corona and climate change.

Corona as castigation in times of contagion.

St Stephen’s Cathedral empty benches with the pictures of the believers on Easter Mass, 12 April 2020. Photo: ©ERZDIÖZESE WIEN

Lately, religious programs on Austrian radio and television have ratings that make every streaming service fade in comparison. But most Viennese still seem to have invested their hopes in a more profane cult: consumerism. Or, more precisely, the opening of stores after Easter.

Chancellor Sebastian Kurz – who has been described as a Messiah of conservative politics – has literally spoken of a “resurrection”. After a month of tough restrictions, Austria is now taking a cautious step back to something at least reminiscent of the normality that prevailed before Wuhan and Ischgl, the ski resort in the Tyrolean Alps that became one of Europe’s worst hotbeds of the coronavirus.

This is all about relieving pressure. About letting citizens, who have sacrificed so much to help flatten the curve, believe in a future not too dissimilar to what once was. And, of course, it’s about saving what can be saved of the economy. Setting the wheels in motion. Sure, epidemiologists warn that a second viral wave could very well come with the purchase – but Chancellor Kurz, virtuous and vigilant, stands ready to slam the emergency brake.

However, though queues now ring the city’s home improvement stores and car washes, the Easter miracle will have to wait. The Graben is almost as deserted now as it was a week ago. Typically, shoppers on the Graben are not Viennese, but Russian, Chinese, Italian… And they are not around anymore.

Last New Year’s Eve alone, about one million visitors walked past the Plague Column. More than 15 percent of Austria’s gross domestic product comes from tourism. Before das Riesenrad – the Ferris wheel in the Prater amusement park – has started moving again it will be hard to claim that the wheels of the economy are turning. Before the foreign guests have returned to both Graben and Tyrol, no one will even think of erecting a Corona Column.

Post-pandemic normality is still far off. Even Chancellor Kurz knows that.

This wheel is not turning. The famous Riesenrad, from which Orson Wells’ Harry Lime, in the film The Third Man, looks down on the little people moving around in post-war Vienna, comparing them to dots. It would mean nothing, he says, if one of them or a few of them “stopped moving, forever”. Photo: ©CHeFred

.