“Just watch out if you go into the forest on your own. It can be dangerous in there. Strange things can happen. Some people have never made it out again.” That is what they said to the lanky man in the glasses. He was threatening to tell all, to lift the lid on the whole system of illegally harvested timber and the trade in it. He himself was part of that system, but he was prepared to get out of it and risk everything as a result.

The transformation of trees into boards involves a process of gigantic dimensions. Columns of articulated lorries deliver the logs to huge timber yards day and night. Here they are seized by gripper arms, measured by computer, and a worker in the driver’s cab assesses the quality of the wood. And then they are flung onto a conveyor, turned over and rotated, stripped of their bark, and fed into the sawmill machine. 40 tree trunks every minute, 2400 every hour, 28800 every shift. Romania’s biggest processor, a colossus in the sector, has an insatiable hunger for wood. And that processor is an Austrian, holder of the Silver Medal of Honour of the City of Vienna, owner of grand palaces in the heart of the city and a secretive man: Gerald Schweighofer. The business magazine Trend once published an article about his rise from humble beginnings in Lower Austria’s Waldviertel region, in which it referred to the 61-year-old as a “hard-as-steel timber baron”.

A Google search on “Schweighofer” and “Romania” produces less attractive-sounding results: in May last year the media were full of reports about raids on his sawmills carried out by the Romanian anti-mafia unit. Schweighofer staff stood accused of having formed an organised criminal group and being involved in illegal logging, tax fraud and unfair commercial practices. “Investigations into our former employees are still ongoing; we are assisting the Romanian authorities and will not be making any further comment,” says a man who seems to find it all rather embarrassing but who ultimately owes his job to the unpleasantness. His name is Michael Proschek-Hauptmann, since 2017 the public face of change at Schweighofer.

Caught up in its own chipping machine

Responsible for compliance and sustainability, Proschek-Hauptmann is an acknowledged expert in environmental issues and has made the journey from Vienna specially in order to give Addendum a guided tour of one of the Schweighofer mills in the Transylvanian town of Sebeș. Until recently, any visits by journalists ended at the gate. It had even been known for activists who had followed the illegal timber trail this far to be pepper-sprayed by security staff.

But the newly decreed watchword is openness. For the Austrian company is under serious suspicion of involvement in the illegal logging of the last remaining major contiguous areas of forest in Europe. Schweighofer has been stripped of its prestigious Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification of sustainably produced timber. The 110-page report of the FSC investigation, which has been seen by Addendum, refers to “clear and convincing evidence” that Schweighofer was “involved systematically […] directly and indirectly, in the trade of timber which has been harvested and/or handled in violation of existing laws and regulations” and had associated “with individuals and companies with criminal and corrupt backgrounds”.

And this when what is at stake in Romania is a unique natural paradise that is even more important in the face of climate change, home to wolves, bears and lynxes, as well as to a host of plants that have long since died out elsewhere. And while climate activists are trying to reduce CO2 emissions through flight-shaming and demands for driving bans in cities, a single 150-year-old beech tree absorbs nine tonnes of CO2 – enough to offset a journey of 56,000 kilometres by car.

Yet these and even older trees are being indiscriminately felled. For these trees are also a business – a business that engenders greed that in turn leads to violence, threats and in one instance even attempted murder.

The arrival of the Austrians

No history of the depletion of the Romanian forests would be complete without the role of Austrian businesses and the families behind them. It is a role that leads to places of which Michael Proschek-Hauptmann, the benevolent face of the Schweighofer concern, is reluctant to speak. And it leads, too, to the question of responsibility – not just for Schweighofer, but for other Austrian companies too.

The names of these companies are not well known to the general public, even though they are world market leaders in their respective branches of the global timber exploitation chain. And even though no one directly employed by them ever fells a single tree themselves, they stand accused of commercial complicity in deforestation.

With the aid of satellite images, Global Forest Watch has calculated that 317,000 hectares of Romanian forest were lost to logging between 2001 and 2017. That’s the equivalent of 444,000 football pitches or twice the size of the Austrian federal state of Vorarlberg. Half of these trees were in national parks or conservation areas and were hundreds of years old. Experts from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a US NGO, investigate and expose the predatory exploitation of nature throughout the world.

“Whether it’s in America, Asia or Africa, people are appalled at the way our planet is being destroyed. But while the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest has been horrifying people for years, hardly anyone realises that Europe contains remnants of virgin forests that are just as important. The fact that the majority of these are on our doorstep, in the Carpathians, and are under threat remains an untold story,” says the EIA’s David Gehl. The EIA reports accuse Schweighofer of having been the “biggest receiver of illegal timber” and having “lied about the source of its products for more than ten years”.

260 million fallen trees

The giants in the timber sector must have thought they’d hit the jackpot when they first discovered a new Eldorado for themselves: Romania, one of the poorest countries in the EU. One of those giants was Schweighofer. From 2002 onwards it started selling its sawmills in Austria, taking its profits (reportedly in nine figures) and using them to build vastly bigger structures in Romania. Romanian politicians welcomed the arrival of the Austrians. It would, after all, prevent the thousands of tiny sawmills across the country forming conglomerates whose owners might have decided to take a political hand themselves. Schweighofer now has more than 3,000 staff, a turnover of 762 million euros and five factories in the country, producing pellets and sawn, glued and profiled timber that it sells throughout the world, including in Austrian DIY stores.

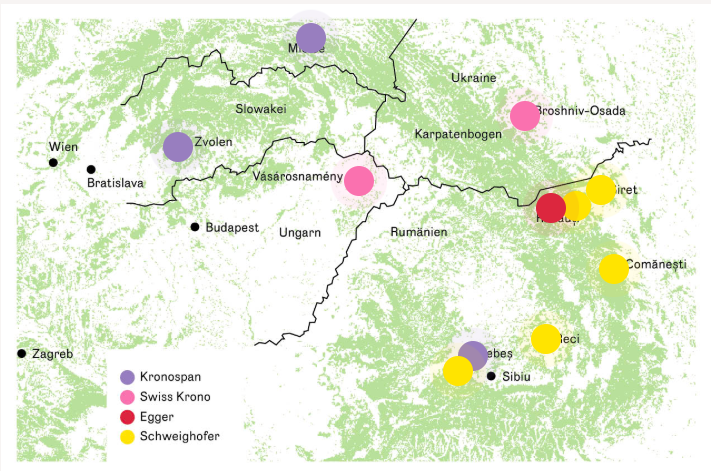

There is also the Kronospan company. Part of the Salzburg-based Kaindl industrial dynasty and with an annual turnover of more than two billion euros, it is the world’s biggest manufacturer of wood-based panels, numbering Ikea among its customers. Together with their Swiss sister company, Swiss Krono, the Kaindls are one of the main players in the Carpathians as a whole.

And finally there is also their competitor, the Tyrolean company Egger, owned by brothers Michael and Fritz Egger, who have built up a global concern with 18 sites in eight different countries. As suppliers to the furniture trade, the timber trade and DIY chains, they too set up in Romania. It is no coincidence that both Kronospan and Egger built their factories right next to those owned by Schweighofer. To this day they remain part of the same exploitation chain, obtaining wood shavings and wood scraps from Schweighofer for further processing into panels, so they are all interconnected.

Austrian timber processing plants in the Carpathians, by company:

Once they had staked their various claims and signed contracts, and the notoriously corrupt Romanian state forestry company, Romsilva, had issued their logging licences, they could get started – since the arrival of the Austrians in 2003, some 260 million Romanian trees have been felled.

Threatened and beaten up

“We want nothing to do with any of that. We do not kill virgin forests,” Schweighofer’s sustainability manager, Proschek-Hauptmann, stresses right at the start. He nimbly dodges every attempt to raise the subject of the company’s past, preferring to present reports, show figures, point to the company’s specially developed GPS truck-tracking system. This system is supposed to verify the source of every single tree and substantiate Schweighofer’s apparent reformation into a company that no longer accepts timber from national parks.

The longer we listen to him and the further we follow him through the enormous production plant in Sebeș, the more inclined we are to believe him. Or would be, at least, if it weren’t for the men who risked their lives to prove how the Austrian timber giant conducted itself before it adopted its apparent transparency. Andrei Ciurcanu is one such man. Powerfully built, he could have been a logger himself had he not decided to dedicate himself to tracking down the people who were destroying his homeland forests. Ciurcanu spent many hours struggling through the wilderness, many days on the lookout, and many months documenting the manoeuvres he had witnessed.

He also made many of the horrifying films showing today’s moonscapes where forests of mighty giants once stood.

OUT OF CONTROL from AGENT GREEN on Vimeo.

He and Gabriel Paun, his boss at the environmental protection NGO Agent Green, were threatened and beaten up by unknown persons. On one occasion the brake cable on their car was cut. Another time Paun was sent an email purporting to be from Florian Klenk, editor-in-chief of Falter, an Austrian weekly news magazine. Unsuspecting, he opened both the email itself and the file attached to it, only to find that it was not from Klenk at all but was actually a virus attack that wiped six gigabytes of data from his computer and then prevented him from re-starting it. Paun and Ciurcanu have since become extremely careful when carrying out their research.

“Right from the start, Schweighofer built its entire business model on the legal purchase of illegal timber. They knew it, they tolerated it, and sometimes they actually encouraged it. And it’s not just me saying that: it has been confirmed by investigators from the Organised Crime Unit,” said Ciurcanu, speaking in Bucharest before Addendum’s visit to the Schweighofer plant. “And now, all of a sudden, they want us to believe they’ve turned ‘green’?” Ciurcanu stresses each letter to make it clear that, after all these years, he simply doesn’t believe them.

On the trail of the timber

Ciurcanu points to his most recent investigations which, he says, show that only the Schweighofer modus operandi has changed. Many suppliers do not deliver the timber to the sawmills straight from a commercial forest, but instead take it to storage yards, some of them on the edge of the national park. There they are able to mix legally and illegally felled timber together, before it is declared clean and supplied to the timber giant. In the case of Schweighofer, he says, this allows them to bypass the GPS truck-tracking system, since that only records the journey from the storage yard to the sawmill. Moreover, Schweighofer continues to purchase timber from suppliers who log in national parks, merely requiring them to keep this national park timber separate from the rest at the storage yards.

Back in the Schweighofer plant in Sebeș, Michael Proschek-Hauptmann has managed to pack his two years’ activity as Sustainability Manager into a two-hour guided tour. He has denounced the corruption in the country, praised Schweighofer’s security systems and persuasively argued that the company is making a genuine effort to rectify the mistakes of the past. As recently as 2015, however, the EIA secretly filmed a meeting between a Schweighofer manager and some people posing as potential suppliers at which the manager was apparently willing to accept timber from dubious sources on an extra-contractual basis.

Proschek-Hauptmann challenges this: “The only thing the manager in question admitted in this film was that he would accept quantities over and above those specified in the contract. That is common practice in the timber industry.” He goes on to say that the manager had made a sworn statement to Schweighofer, confirming that the discussion had not gone off in any other direction. So it is rather astonishing, then, when Proschek-Hauptmann goes on to say that the company – which says the manager did nothing wrong – nevertheless terminated his job.

Proschek-Hauptmann claims to have everything in hand where the controversial timber storage yards are concerned, too. “These are strictly regulated facilities: they keep registers, they record deliveries, and everything can be checked.” According to their own figures, though, nearly half of Schweighofer’s Romanian timber, which also goes to the neighbouring Kronospan and Egger companies for further processing, does not come direct from the forests but from storage yards like these. For this reason, the EIA says it is naïve of Austrian companies in this often criminally corrupt environment to suddenly put their faith in the honesty of their Romanian suppliers.

The environmental agency accuses them of continuing to do business with companies that are still illegally logging in the national parks. Proschek-Hauptmann hesitates for a moment, then says, “We have developed internal control systems and introduced a requirement for every storage yard operator to be visited by us at least once a year, and more frequently if there are any suspicions about them.” According to Schweighofer, this policy has recently led to the suspension of eight of their 650 or so suppliers. Yet even now, the company’s GPS tracking system is unable to monitor the source of each individual log in half of its Romanian timber.

“All of this cleared land lies within national parks or the Natura 2000 nature protection network,”

It is late now in Sebeș, the small Transylvanian town that is host to two Austrian timber companies next door to each other: Schweighofer and Kronospan. Matthias Schickhofer is in town. He comes from Lower Austria and is a photographer with several books to his name. In them he portrays the beauty of Europe’s last remaining virgin forests and describes the threat they face. Working with Euronatur, a German conservation foundation, he has been focusing on Romania for a long time now and is currently organising a scientific conference here on the protection of virgin forests. For even though two-thirds of the surviving virgin forests of Central Europe are located in Romania – as much as 200,000 hectares – only about one-tenth of this amount is under any kind of protection.

Little action, much wood

To illustrate the problem, Schickhofer opens Google Earth on his computer. He flies over the densely forested Carpathian Mountains on his screen and zooms in. Where just a few years ago there was still dense beech forest, there are now huge gaps, looking like brown stains in the midst of the green. “All of this cleared land lies within national parks or the Natura 2000 nature protection network,” he says. “The state forestry authorities seize on any small-scale bark beetle infestations or storm damage as an excuse to clear whole hillsides one after another.” He fast forwards on the screen to bring up the latest satellite images of the area – and suddenly, where once there was virgin forest, now there is nothing. The brown patches used to be just scars on the forest; now they are all that is left – a single brown patch of bare land.

“Brussels should be exerting real pressure to stop the conglomerate of state forestry departments, old networks and corrupt clans destroying the last remnants of these virgin forests. It worked in Poland, where the European Court of Justice stopped the logging of the Natura 2000-protected Białowieża Forest by threatening heavy penalties.”

End of Part I.

👉 Original article at Addendum.